“Man differs from the animal by the fact that he is a killer; he is the only primate that kills and tortures members of his own species without any reason… and who feels satisfaction in doing so.” — Erich Fromm, The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness.

Throughout the world, many people suffer from some form or other of mental illness. Of these, a substantial number are also inclined to various expressions of aggression. When conditions arise to dignify their irrepressible violent urges under the purifying rubric of some “higher cause” — such as revolution, rebellion, or jihad — some will gratefully seize upon those “exculpatory” opportunities.

There is a singularly important lesson for the West’s growing struggle against terrorism. It is that in many instances, the events that occur in religion and politics do not do so for the reasons given. Rather, allegedly noble causes that are ascribed are merely after-the-fact rationalizations of certain barbarous human inclinations.

“Homo homini lupus,” said Freud: “Man is a wolf to man.” In essence, this observation lies at the heart of all forms of terrorism, as it also does of war, genocide, and many iterations of violent crime. It follows that if we should ever really want to declare a sincere “war on terrorism,” we would first have to seek beyond the usual assemblage of military remedies. They can generally never exceed a more-or-less futile tinkering at the margins of what is really most important.

Years back, Harold Lasswell, the great American political scientist, described political figures as those who would “displace their private motives on public objects, and rationalize the displacement in terms of public advantage.” What he meant by this psychological explanation was that the core motives of politicians may be deeply personal, relate primarily to apprehensions over deference or status, and still be reassuringly justified or “sanitized” by their owners in terms of some elevated motive. No candidate for the American presidency will ever acknowledge that he or she is running for office to maximize compelling private needs, but all candidates will readily affirm that they have somehow been “called” to rescue an imperiled nation from one or another of the “usual suspects.”

Today, we see that such public kinds of rationalization and displacement are not confined to ordinary politics. On the contrary, we can recognize that these dynamics already animate a fair number of modern terrorists, especially ISIS and other assorted jihadists.

To be sure, there is no scientific way in which determinations of motive can be usefully foreseen or diagnosed.

Nowadays, the standard characterization for seemingly eccentric terrorist foes is “lone wolf,” but even if we should prefer to preserve this otherwise apt analogy, it is also essential that we first begin to understand something more: The emotional dynamic that may set off a terrorist may well not be any genuine commitment to some cause or other, but rather a convenient and accessible opportunity to dignify ordinary criminal impulses.

In the absence of such a useful justification, such criminal behavior would simply be inexcusable. With a self-serving justification, however, it can become a “heroic” act of revolution, liberation, or “martyrdom.” For the perpetrator — and mental illness surely does not preclude high intellectual capacity — an available metamorphosis of criminal violence into permissible and even celebrated forms of presumed obligation could be most welcome.

After all, this sort of transformation offers nothing less than the conversion of evil into good; indeed, at times, even something sacred.

For today’s terrorist, whether in Paris, Orlando or Nice, the mass murder of noncombatants is a typically satisfying expiation, a scapegoating operation that brings to mind certain ritualistic processes of bloodletting, religious sacrifice and an outlet for sadistic sexual excitement. For the jihadist in particular, terror may find a ready ideological shelter in Islam, but the expressed theology is likely little more than a useful cover for acting on otherwise forbidden wishes. The ready supply of adherents only indicates how widespread these forbidden wishes are — but have little to do with politics.

“Man seeks for drama and excitement,” wrote Erich Fromm, “but when he cannot get satisfaction on a higher level, he creates for himself the drama of destruction.” As to the prescribed sacrifice of innocents, whether in Florida, France or anywhere else, a bloodletting furnishes the prospective terrorist with (1) a seemingly incomparable outlet for those grievously violent impulses that would otherwise require self-restraint; and (2) an opportunity to disguise variously grotesque forms of murder as “faith.”

In the end, terrorism as an answer to psychic wishes is plausibly inseparable. But how can one build, pragmatically, upon this complicating factor in creating a more effective strategy for counter-terrorism? If there are literally millions of remorseless and deeply troubled individuals across the world who might crave just a “drama of destruction,” and who could discover a justification in religion or other “high” motives, what can be done to identify and to neutralize them? The sheer numbers involved are overwhelming.

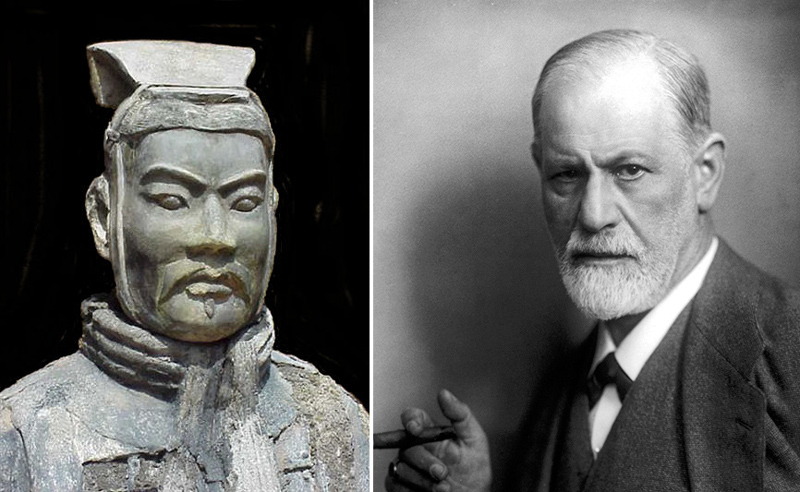

In the end, our operational plans concerning jihadist terrorism may need to be more consciously structured as much upon the cumulative wisdom of Sigmund Freud, Erich Fromm and others as upon Sun-Tzu or Clausewitz.

Our operational plans concerning jihadist terrorism may need to be more consciously structured as much upon the cumulative wisdom of Sigmund Freud (right), Erich Fromm and others as upon Sun-Tzu (left) or Clausewitz. |

More than anything else, this means taking care to consider all killing not solely expressions of politics or religion; and creating more suitable “firewalls” between psychopathic behavior and “political” outlets. This last recommendation must depend upon prior efforts to disabuse individuals of a seductive notion: that terrorism can offer would-be killers a pleasing path to personal sacredness and eventual redemption.

Louis René Beres is Emeritus Professor of International Law at Purdue University. His latest book is titled Surviving Amid Chaos: Israel’s Nuclear Strategy.