When a 25-year-old, known just as Riyanto, entered the Eben Haezer Church of Pentecostal Assembly in East Java on Christmas Eve of 2000, he did not know that his life was about to end. He had been aware, however, of the risk he was taking by being there altogether, particularly on Christmas Eve. As a member of the Banser — the youth wing of Indonesia’s largest Muslim cultural organization, the Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) — he had already made the choice to sacrifice personal safety to protect Christians from falling prey to radical Islamists.

Shortly after mass, as parishioners began to exit the Protestant house of worship, the reverend handed Riyanto and other guards at the entrance an unattended bag he had found among the pews. Looking inside the package and realizing that it contained a bomb, Riyanto took swift action. “Get down!” he called out to all those who were still inside the building.

But Riyanto himself did not duck. Instead, he clutched the explosive tightly to his chest, in an effort to prevent mass casualties. Within seconds, Riyanto was blown to bits.

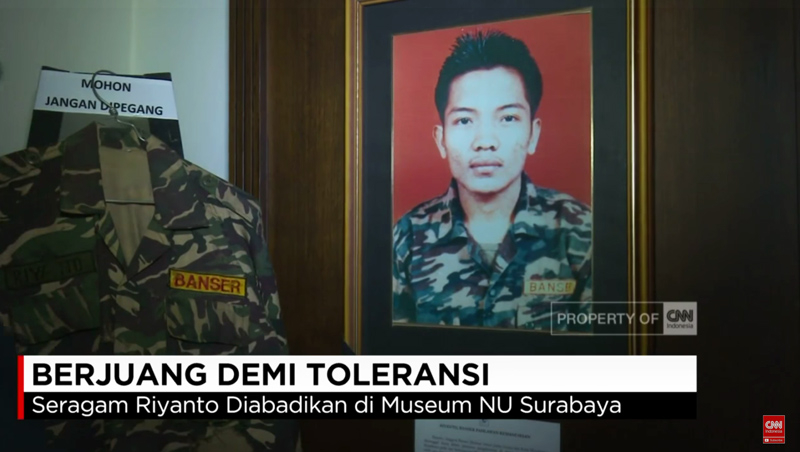

Riyanto was one of four Banser members guarding the church in Mojokerto, a small town south of Surabaya, Indonesia’s second-largest city. His name, like his heroic death, is hailed among moderates in the Muslim-majority country as a symbol of its credo of Bhineka Tunggal Ika (“Unity in Diversity”), which crosses all party and religious lines. His uniform is even on display at the NU Museum.

A photo of Riyanto, displayed alongside his uniform, at the NU Museum in Surabaya, Indonesia. (Image source: CNN Indonesia video screenshot) |

Every year since his death, the Wahid Foundation — named after Indonesia’s fourth president, the late Abdurrahman Wahid (known familiarly as Gus Dur) — has presented awards in Riyanto’s honor to hundreds of students in state and religious schools, with the goal of encouraging tolerance and peace.

To keep Riyanto’s memory alive in the minds of moderate Muslims, the Mojokerto municipality named a street after him. In addition, every Christmas, the Eben Haezer congregation dedicates a prayer to him. Last Christmas Eve, the head of East Java’s Banser Regional Coordination Unit proposed that the anniversary of Riyanto’s death be marked as the “Day of Humanity.”

The practice of guarding houses of worship in Indonesia began in 1965, when the country’s Communist Party launched a coup against the government and killed oppositionists. When Suharto became president in 1967, the practice was no longer necessary and came to halt. But it reemerged during the post-Suharto “reformation” era, which began in 1998, and hardline groups began attacking Christians, raiding their churches and looting their property.

Riyanto was one of many Muslims who answered the great President Gus Dur’s call to express the “true strength of Islam” by safeguarding religious minorities. This multicultural outlook was the cornerstone of the NU. Today, a growing number of Muslims in Indonesia are going against this current. They consider it a sin even to say, “Merry Christmas,” let alone allow those who celebrate it to do so in peace. It is now more crucial than ever, therefore, to hold up Riyanto’s legacy as a reminder of the past and a light for the future.

Jacobus E. Lato, an author, is based in Surabaya, Indonesia.