In the Saudi Kingdom, the primary source of law is the Islamic sharia, based on the principles of a school of jurisprudence (Hanbali) found in pre-modern texts. Ultra-puritanical judges and lawyers form part of the country’s Islamic scholars.

But there is another main source of law: royal decrees. Simple death penalty along with beheading, stoning to death, amputation, crucifixion and lashing are common legal punishments. In the three years to 2010, there were 345 beheadings. But the legal system is usually too lenient for cases of rape and domestic violence.

The common punishment for offenses against religion and public morality such as drinking alcohol and neglect of prayer is usually lashings. Retaliatory punishments are also part of the legal system, such as, literally, an eye for an eye. Saudis can also grant clemency, in return for money, to someone who has unlawfully killed their relatives.

It is not surprising to anyone that Saudi Arabia is widely accused of having one of the worst human rights records in the world — the Kingdom is one of the few countries in the world not to accept the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights. There is capital punishment for homosexuality. Women are not allowed in public places to be in the presence of someone outside the kinship. They are not allowed to drive.

But what makes Saudi Arabia an even uglier country than all of that medieval legal absurdity and systematic and cruel torture of its own citizens combined, is the fact that those pre-modern laws do not apply to all Saudis. One powerful visual evidence of this was a few photographs showing a Saudi prince vacationing on an ultra-luxurious yacht off Turkey’s Mediterranean coast. The very strict Quranic ban on all forms of extravagance and the command for modesty are probably not printed in Saudi copies of the Muslim holy book. But there was more than that.

Prince Nawaf al Saud spent four days with his friends and bikini-clad Swedish models on the yacht, which he rented for one million euros for a week, and was photographed partying all day. There were reports of a 4,500-euro dinner on a nearby Greek island and 1,000-euro tips for the waiters. Turkish columnist Ahmet Hakan wrote that the prince could have accommodated at least 80 Syrian refugees with the million euros spent for the chartered yacht:

“You in your country immediately draw your swords if a poor Bangladeshi [laborer] has accidental eye contact with a woman in her full niqab … What does your [holy] book say about your extravagant partying with models in bikinis?”

Good question.

But Turkey saw another Saudi prince recently. Business magnate, investor and, according to some, philanthropist Al-Waleed Bin Talal visited a Turkish resort on the Mediterranean coast shortly after Turkey’s failed coup of July 15.

Al-Waleed is a grandson of Ibn Saud, the first Saudi king, and a half-nephew of all Saudi kings since. Forbes listed him in March as the world’s 41st richest man, with an estimated wealth of $17.3 billion. While in Antalya, the Turkish resort, he was interviewed by the leading Turkish daily, Hurriyet. His messages were:

- “When the coup took place in Turkey I said to myself I should go to Turkey immediately [in solidarity with President Erdogan].”

- “Erdogan and I defend a ‘progressive Islamic’ understanding.”

- “Some say that Islam and democracy cannot cohabit. But the Turkish example shows that this [argument] is totally invalid. Turkey is the best indication that Islam and democracy can cohabit. It is a country that is taken as precedent. We can see how much Turkey could internalize democracy.”

If the honorable prince was not joking, he must have come to Turkey to tell millions of Turks suffocating under Erdogan’s autocratic regime fairy tales from an Arab kingdom. With the third-world democratic culture it features, Turkey can be taken as a precedent only by North Koreans, almost all inhabitants of the Gulf and Arab countries and by Iranians. Apparently, what the prince understands of democracy is a totally different thing than what the term means in more civilized parts of the world.

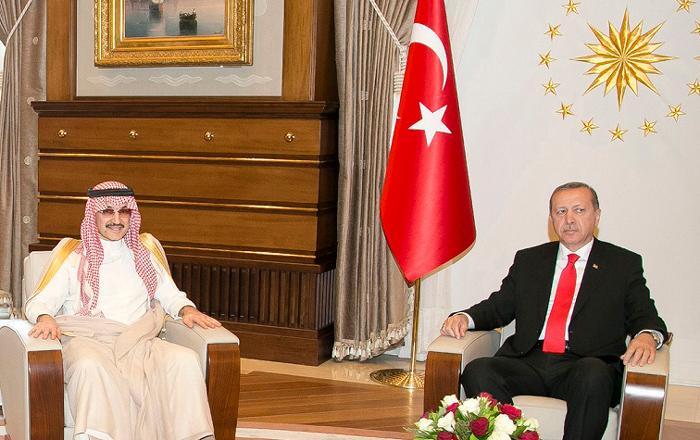

Saudi Prince Al-Waleed Bin Talal meets with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Ankara, May 6, 2015. |

And if Prince Al-Waleed so passionately defends democracy, he should spend less of his office time in showing solidarity with undemocratic leaders, and more in giving at least a bit of democratic breathing space to his own people.

Burak Bekdil, based in Ankara, is a Turkish columnist for the Hürriyet Daily and a Fellow at the Middle East Forum.