The “Cat and Mouse” Problem of Hunger Strikes in Prison by Paul Leslie September 1, 2015 at 4:00 am

-

The European Court of Human Rights ruled that in situations where hunger strikes are organized as a means of pressuring the relevant authorities into releasing detainees, a refusal to comply with the demands of the hunger-strikers does not constitute a violation of Article 2 — provided that there is a regulatory system in place guaranteeing all the necessary measures are taken to monitor and manage these situations, including unrestricted access to appropriate medical care.

-

-

Israel has the benefit of the European Court rulings to refer to, as well as the provisions many fellow democracies have on their statute books concerning the membership of proscribed groups and the criteria for proscribing them — in the case of less liberal democracies like France, they are more wide-ranging than those applied in Israel.

Israel has a dilemma. Is it better when confronted with hunger-striking “activists” belonging to terror groups to let them starve themselves to death or not to let them starve themselves to death, even if it means feeding them by force.

In Britain, for instance, decisions about force-feeding in prisons have in general been governed by legislation that relates to the medical profession — and in particular those laws which pertain to mental health and mental incapacity — as well as being influenced by considerations linked to the criminalisation of aiding and abetting suicide.

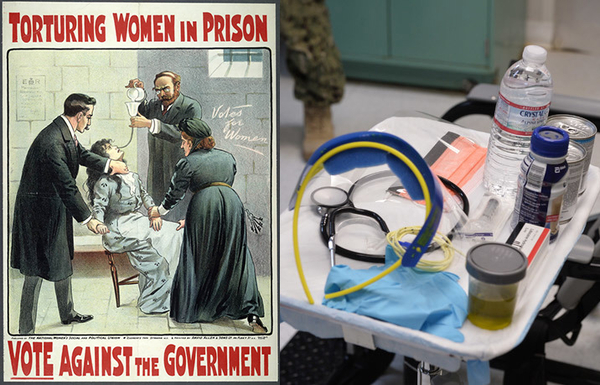

There has been nothing on the statute book specifically relating to hunger-striking detainees with the exception of the Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill-Health) Act. This was adopted in 1913 by way of response to a specific set of historical circumstances. Suffragettes who were imprisoned for public order offenses and related illegal activities had embarked on hunger strikes.

The law, given the popular nickname of the Cat and Mouse Act, allowed hunger-striking prisoners, whose fasting had placed them at risk of death, to be temporarily discharged. Once their health was deemed to have been restored, they were to be recalled to prison to complete their sentences.

In a suffragette-related case, Leigh v Gladstone, of 1909, it had been held that the Home Office had a duty to preserve the lives of prisoners. Even after the passage of the 1961 Suicide Act, the management of hunger strikes in British prisons was largely dictated by the fear that allowing fasting prisoners to die might be considered aiding and abetting suicide. Consequently, force-feeding prisoners when considered medically essential continued to be the general practice.

Force-feeding, then and now. |

This state of affairs changed after the statement in House of Commons by Roy Jenkins on 17 July 1974, in connection with the hunger striking Price sisters: “The doctor’s obligation is to the ethics of his profession and to his duty at common law; he is not required as a matter of prison practice to feed a prisoner artificially against the prisoner’s will.”

Henceforth, policy in the management of hunger strikes was no longer uniform and became more complex. (Australia is still influenced by British legislation and case law in this area.)

While French law upholds the right of prisoners not to be submitted to any medical treatment to which full and informed consent has not been given, in accordance with Article D. 362 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, it also permits force-feeding under medical supervision in situations where it has been determined by independent medical professionals that there has been such a deterioration in the physical condition of the hunger strikers that there is an immediate risk to their lives, in accordance with Article D. 364.

According to a ruling issued by the French Conseil d’État on August 16, 2004, in cases where there is an opportunity to do so, the physicians concerned must make all the necessary efforts to inform reluctant patients of the consequences of their decision to refuse treatment.

As far as the United States is concerned, cases involving force-feeding — which has never been found to be unconstitutional in cases where there is an immediate threat to life — have been considered at both federal and state level.

There have been, and continue to be, divergences in the ways different states manage hunger strikes in penal institutions.

Germany has specific legal provisions directly addressing the situations in which force-feedingmight be carried out — whether in prisons or in institutions where there are patients suffering from some forms of dementia, or from conditions which temporarily present as dementia.

In 1999 Muharrem Horoz, a sometimes violent opponent of the Turkish government, was placed in preventive detention by the Turkish authorities. He had been arrested for involvement in subversive activities against the Turkish state and various terrorist acts, including involvement in a bomb attack against the governor of Çankin. In 2001, to protest high security Turkish prisons that, instead of dormitories, accommodated cells that held one-to-three people, Horoz embarked upon a series of hunger strikes. He was hospitalized several times; but after his application for a release was rejected on the grounds that he had access to medical treatment, his hunger strikes culminated in his death on August 3, 2001.

His mother claimed that his right to life, guaranteed under Article 2 of the European Convention of Human Rights, had been violated. She petitioned the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). But its ruling of 31 March 2009, Affaire Horoz c. Turquie (petition 1639/03), confirmed that a majority of the judges found not only was it impossible to establish a causal link between Horoz’s death and the refusal of the authorities to release him, but that, by ensuring that the detainee had full uninterrupted access to medical care and to any treatment deemed necessary, dispensed by fully qualified medical professionals, the Turkish state had satisfied its obligation to sustain him.

The ECtHR ruled that in situations where hunger strikes are organized as a means of pressuring the relevant authorities into releasing detainees, a refusal to comply with the hunger-strikers’ demands does not constitute a violation of Article 2 — provided that there is a regulatory system in place guaranteeing all the necessary measures are taken to monitor and manage these situations, including unrestricted access to appropriate medical care.

The Court determined that Horoz’s decision had been made freely, without any constraint, and that he was in full possession of his mental faculties, so that the Turkish authorities had the right to accept Horoz’s refusal of medical intervention, even if his refusal led to his death.

Bernard Rappaz is a repeat offender and serial hunger striker who has been imprisoned more than once for a number of offenses, including fraudulent activities and drug trafficking. On 20 March 2010, he began a hunger strike to protest, he said, the excessive severity of his prison sentence — five years, eight months – as well as the criminalization of the use and sale of cannabis. After being temporarily discharged by the authorities — for fifteen days in May 2010, during which time he ceased his hunger strike and was provided with the all the medical care required — he was returned to prison, where he resumed his hunger strike; but this time the authorities refused to consider any further temporary release. They instead upheld the principle — given legal force in Article 92 of the Swiss penal code — that prison sentences should be served without interruption, except in exceptional circumstances.

Rappaz was allowed to exhaust all the avenues of legal appeal against this decision, and several doctors were consulted by the penal authorities on this matter. Rappaz, in detention, continued to receive constant medical supervision — whether in his cell, or in hospital. When his hunger strike had finally weakened him to the extent that he was at risk of death, and he had been informed by qualified professionals of all the medical consequences of his hunger strike, the decision was made at the beginning of November to feed him, despite the opposition to force-feeding that had been expressed by several doctors. On 24 December 2010, he ended his hunger strike.

In a ruling by the ECtHR dated 26 March 2013, Bernard Rappaz contre la Suisse (petition 73175/10), a majority found that there were no grounds to condemn the Swiss authorities. Unlike other cases of force-feeding, where the rights of petitioners “not to be subjected to cruel or inhuman and degrading treatment” had been found to have been violated, the Swiss ruling found that the decision to feed Rappaz forcibly had been made in response to an immediate threat to his life, solely to satisfy a clear medical necessity and not to maintain discipline, or to break the will of the prisoner, or any other non-medical reason. Moreover, they ruled, the medical means to save his life did not inflict unnecessary or disproportionate suffering.[1]

Currently, Israeli authorities entrusted with the detention of potential or actual murderers belonging to terror groups whose ultimate aim is Israel’s destruction, have recently been faced with same painful “Cat and Mouse” decision as European countries: whether to allow hunger strikers to fast to death, give in to their demands, or force-feed them. Israel has the benefit of being able to refer to the ECtHR rulings. The rulings apply both in cases of prisoners convicted in regular criminal proceedings, and also in cases of security detainees against whom it is judged not (yet) advisable to present evidence, in order not to jeopardise intelligence contacts.

There are plenty of arguments that can and should be used to defend Israel from any unjust attacks directed against it regarding its treatment of hunger strikers.

It is also important to refer to the provisions many fellow democracies have on their statute books concerning the membership of proscribed groups and the criteria for proscribing them. In the case of more illiberal democracies like France — which allows for the banning of groups rightly or wrongly deemed racist, as well as having specific statutes that punish severely its equivalent of “criminal conspiracy” (“association de malfaiteurs”) where terrorism is involved — they are more wide-ranging than those applied in Israel.

Paul Leslie is an independent journalist living in London. He has degrees from Exeter College, Oxford University and the Sorbonne, where he received a doctorate.

[1] An analysis by Yonah Jeremy Bob, published by the Jerusalem Post on 17 June 2014, shortly before the adoption of a new law — incorporating all the necessary safeguards, both medical and non-medical and specifically permitting and regulating the force-feeding of — highlights the ethical or moral issues raised when decisions are made either to order the force-feeding of detainees or to allow them to fast without intervention, even if this leads to their deaths. The article also discusses the conflicting principles involved, and gives examples of the policies adopted by the governments of various democratic states to tackle the challenges of politically motivated hunger strikes.