Following the terrorist attack outside Britain’s Houses of Parliament on March 22, 2017, it was not surprising or wrong that many Muslims denounced the attack and declared it to be un-Islamic. Two days afterwards, Dr. Mohammed Qureshi, chairman of the Board of Trustees for the Shropshire Islamic Foundation, said:

We need to be united in this situation.

We should not give any religion a bad name and these people need to be dealt with in full force and there should be zero tolerance when it comes to dealing with them.

My heart goes out to these victims. And my heart goes out to the people’s families and those who are injured. I pray they all have peace in their minds.

He added:

There is no place for these acts in the religion of Islam.

The people are being radicalised and the young and vulnerable people need to be protected.

We need to disassociate this with Islam, as Islam is a religion of peace.

This view was echoed in a press release by the Foundation, in which sympathy for the dead and their families was followed by a commitment to non-violence: “as a community, we need to come together to condemn violence and hatred and work towards cohesion and tolerance”.

More recently, a document about Islamophobia published by the Green Party of the United States affirmed the purportedly peaceful character of Islam:

The highest goal of the Islamic faith is Peace. Peace is pursued over all and for Muslims the world over, ‘holy war’ has nothing to do with the concept of jihad. The Arabic word translates as ‘struggle,’ and is used a handful of times in the Quran to speak of the struggle to stay on the righteous path, to fulfill obligations to family, community and Creator, what the Islamic scholars call a higher jihad.

These claims, however, seem innocent of the verses that say:

So when you meet those who disbelieve [in battle], strike [their] necks until, when you have inflicted slaughter upon them, then secure their bonds…. And those who are killed in the cause of Allah — never will He waste their deeds. Surah Muhammad [47:4]

Or:

And prepare against them whatever you are able of power and of steeds of war by which you may terrify the enemy of Allah and your enemy and others besides them whom you do not know [but] whom Allah knows. [Sahih International] Verse (8:60)

There are said to be 123 verses in the Quran concerning fighting and killing for the cause of Allah — more than a few.

These claims also show that many people seem to be buying into the narrative of Islam as a perfect religion of peace, even if saying so runs counter to more than 1400 years of history and the official record of classical Islamic scholarship about jihad. Islam, after all, conquered Persia, Turkey, North Africa and the Middle East, Greece, Spain and most of Eastern Europe — until its armies were stopped at the gates of Vienna in 1683.

At the same time, there can be no doubt that Muslim leaders who speak out against terrorism and radicalism need our support and that they must be the very people governments, churches, and the security services speak to and work with if we are to head towards the deradicalisation of Muslim communities in the West. Qureshi’s remarks deserve to be taken at face value. Neither he nor his foundation and its associated mosque and academy has any known links to radicalism. They belong to the largest mainstream form of Sunni Islam, the Hanafi school of Islamic law, and there is no overt reason that Qureshi is not sincere in his belief that Islam is a religion of peace.

At the same time, however, he must know better. His own second name is Mujahid, which means “a fighter in the jihad”. Not only that, but his mosque is, like most others in the UK, Deobandi in orientation; and it is out of Deobandi madrasas [Islamic religious schools] that the Taliban originated. Deobandi Islam, although mainstream, has over the years appealed to Muslims in Pakistan and abroad who have a fundamentalist disposition. Qureshi cannot be unaware of that. It is hard to be a reasonably knowledgeable Muslim and not know that calls for violence pervade the Qur’an and sacred Traditions, or that Islamic armies have been fighting European Christians, Indian Hindus, and others since the 7th century.

What we in the West know is that a string of modern politicians and churchmen in Europe and North America have, like Qureshi, insisted — perhaps in a sometimes-desperate attempt to dissociate Islamic terrorism from the religion of Islam — that Islam is a religion of peace. The violence, they say, is a perversion of Islam, and they say this even as terrorist after terrorist invokes Islam as his motivation and shouts “Allahu Akbar!” [“Allah is the greatest!”] while committing the crime. Terrorist groups, such as al-Qaeda and Islamic State, confidently quote the Qur’an, Traditions [Hadith] and shari’a legislation to justify their attacks.

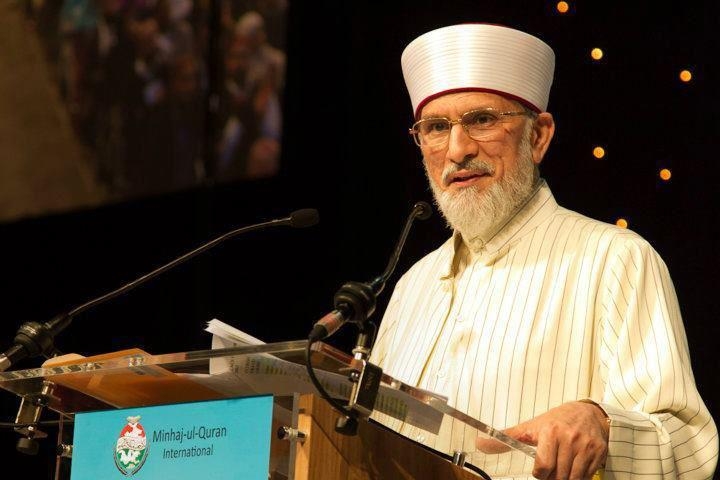

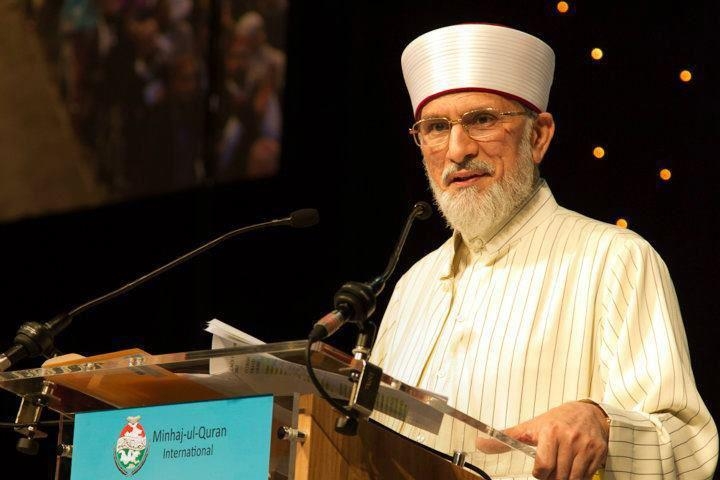

Western leaders often turn to Muslim imams and scholars to confirm their view that Islam is essentially like modern Judaism or Christianity, if not a mirror image of the Quaker religion. A major expression of this approach is a book by a leading Pakistani scholar, Muhammad Tahir-ul-Qadri. Translated into English, this book of some 400 pages is entitled, Fatwa on Terrorism and Suicide Bombings (London, 2010). It has been widely praised as an outstanding authoritative text that demonstrates that terrorism of any kind is contrary to Islamic teachings and law — an argument reinforced by hundreds of citations from the Qur’an, Traditions, and a host of classical Muslim authorities.

Muhammad Tahir-ul-Qadri (1951-) is a scholar and religious leader with an LLB and a PhD in Islamic Law; a politician (he founded the anti-government Pakistan Awami Tehreek party in 1989), and an international speaker. He is touted as having studied since childhood the many branches of religious studies under his father and other teachers, and having authored on Islamic topics one thousand books (not an uncommon claim among Muslim writers). He comes from a Barelvi/Sufi background, the main opposition to Deobandi Islam in Pakistan and abroad. Qadri is also the head of Minhaj-ul-Quran, an international organization that promotes Islamic moderation and inter-faith work.

Qadri and his organization have made a mark on political and religious leaders in many places. On September 24, 2011, Minhaj-ul-Quran held a large conference in London’s Wembley Arena. Qadri and other speakers issued a declaration of peace on behalf of representatives of several religions, scholars and politicians. The conference was endorsed by the Rector of Al-Azhar University (the chief academy in the Sunni Islamic world); Ban Ki-Moon (Secretary General of the UN); Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu (Secretary General of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation); David Cameron (British Prime Minister); Nick Clegg (British Deputy Prime Minister) and Rowan Williams (Archbishop of Canterbury), among others.

It is not surprising, then, that Qadri’s fatwa has made a great impression on many concerned about terrorism instigated and carried out by organizations that lay claim to a connection with Islam. There can be no doubt that a condemnation of Islamic terrorism coming from an eminent Muslim figure is an important contribution to the struggle to contain and eventually eliminate not just the terror but the radicalisation that inevitably precedes it.

At the same time, however, it may be argued that while Qadri presents strong religious rulings that reject acts such as suicide bombings that characterise modern movements as in Islamic State, he fails to prove his claim that, “Islam is a religion of peace and security, and it urges others to pursue the path of peace and protection” (p. 21). His fatwa, in fact, only proves that certain types of violence and certain types of victims are illegal within Islamic scripture and law. It does not show that Islam is, in its essence, a pacifist, peace-loving faith. Let us try to disentangle this.

The fatwa rightly devotes several chapters to important topics: “The Unlawfulness of Indiscriminately Killing Muslims” (chapter 2); “The Unlawfulness of Indiscriminately Killing Non-Muslims and Torturing Them” (chapter 3); “The Unlawfulness of Terrorism against Non-Muslims – Even During Times of War” (chapter 4); “On the Protection of the Non-Muslims’ Lives, Properties and Places of Worship” (chapter 5); and “The Unlawfulness of Forcing One’s Belief upon Others and Destroying Places of Worship” (chapter 6).

This is certainly a massive improvement on the rulings of Salafi sheikhs who support Islamic terrorist groups and issue fatwas to support things such as murder and suicide bombings. The leading Muslim Brotherhood ideologue, Sheikh Yusuf al-Qaradawi, for example, for a long time insisted that suicide bombings carried out by Palestinian terrorists were a legitimate form of self-defence — and his fatwas encouraged other sheikhs to advocate suicide attacks.

The average reader is unlikely to read the entire book; even in a glance through it, much will be missed. One might well assume that Islam, as portrayed by Qadri, opposes terrorism for much the same ethical reasons that Jews, Christians and others oppose it. But a close reading shows that he is operating from a different premise to non-Muslims. His concern is to read everything in a close context of Islamic law — not ethics. This is particularly noticeable in the legal underpinnings he gives to almost everything. He devotes chapters 8-11 (pp.171-237) to an extremely conventional discussion of the evils of rebelling against an Islamic government even if its ruler were corrupt. Terrorists, he asserts, are to be condemned because they take up arms against their governments. By this definition, the rebel groups fighting against Bashar al-Assad in Syria must be condemned because they have taken up arms against their lawful ruler.

He also devotes chapters 12-17 (pp. 239-395) to drawing a comparison between today’s terrorists and the earliest Muslim rebellious group, the Kharijites. The Kharijites emerged after the first schism in Islam, following the assignation of the third Caliph, when they rebelled against both the fourth Caliph, ‘Ali, and the man who became the ruler of the Umayyad Caliphate (661-750), which created the first Islamic Empire. The dissenters shocked followers of the young faith by declaring those with whom they disagreed to be apostates worthy of death. In their first years, they murdered hundreds of Muslims. Their use of terror against other Muslims and their rebellion against the Islamic state earned them a reputation as the greatest threat to the unity of the Muslim world. By focusing so narrowly on the Kharijites in his anti-terror polemic, Qadri reveals that his concerns are based purely on Islamic considerations, not broader concepts of justice. Christians, Jews, secularists, and others, for instance, condemn terrorism as a breach of human rights, Judaeo-Christian ethics, and international law. Qadri is not interested in any of those things, just the impropriety of terrorist actions in relation to Islamic law. This narrow view allows him to ignore the wider questions of violence in Islamic scripture, law, and history.

Qadri’s admirable take on terrorism conceals a large elephant in the room. Islam has for centuries used violence against non-Muslims in what is considered a legitimate manner, through jihad. It is not simply that Muslim armies have fought their enemies much as Christian armies have engaged in war. Jihad is commanded in the later verses of the Qur’an, is endorsed in the Traditions and the biography of Muhammad, and codified in the manuals of shari’a law. Qadri knows this perfectly well, and at times inadvertently reveals as much in several ways.

The word jihad, for example, occurs many times in the fatwa, usually when he refers in footnotes to chapters in the great Tradition collections — records of prophetic injunctions to holy war; the prophet’s own engagements in jihad, or his sending out raiding parties to engage with non-believers. Thus, when Qadri tells us that it is unlawful to kill non-Muslim women and children, the elderly, traders and farmers, and so forth, he is citing the rules of engagement in jihad, and not that holy war against non-Muslims is foresworn in Islamic texts. Everything he cites against the use of terrorism is actually taken from classical sources that explain the rules that apply to fighting jihad; not that jihad is illegitimate.

Qadri does not merely insist that Islam is a religion of peace and security. By tucking all references to jihad in footnotes in transliterated Arabic, he never has to explain what Islam is about and how it relates to his rulings on what is and what is not permissible. He expands on this theme:

“The most significant proof of this is that God has named it Islam. The word Islam is derived from the Arabic word salama or salima. It means peace, security, safety and protection. As for its literal meaning, Islam denotes absolute peace. As a religion, it is peace incarnate.” (p. 21).

A few pages later, he expands on this, writing a long passage “On the Literal Meaning of the Word Islam” (pp. 25-34), interspersed with quotations illustrating this. He correctly links the word “Islam” to the three-consonant root “s-l-m”, which has undisputed connections to concepts of peace and security. He even writes at one point “… every noun or verb derived from Islam, and every derivative or word conjugated (sic) from it, essentially denotes peace, protection, security and safety”.

Just a minute. Qadri is a fully trained Arabist; he even makes references to major Arabic dictionaries. So he really has no excuse for writing such nonsense. It is exactly that on at least two levels. Arabic roots create dozens of words with different meanings, and “slm” is particularly rich in vocabulary. Salma and silm may indeed mean “peace”, but salam means both “forward buying” and a variety of the acacia tree. Sullam means a ladder, stairs, a musical scale, a means, instrument or tool. Salama means “blamelessness, flawlessness, and success”. Salim can mean “healthy” or “sane”. Sulama means the “phalanx” bone. Sulaymani is mercury chloride –there are many more examples.

At a deeper level, most Arabic verbs can have up to fifteen (more usually ten) forms, each with different meanings. The root that Qadri relates to peace has almost no forms that relate to peace at all. The fourth form, aslama, is the one that gives us the verbal noun islam. The fourth form has several meanings, none of which refers to peace. Instead, it means “to forsake, leave, abandon, to deliver up, surrender, to resign oneself or to submit”. The most reliable Arabic-English dictionary by Wehr translates islam as “submission, resignation”, including submission to the will of God. Unfortunately for Qadri, therefore, Islam does not mean peace. The word for peace is salam. The word Islam means, unambiguously, submission [to the will God or Allah].

Let us return to Chapter 5, where Qadri inadvertently reveals the extent of the pretence he is making that Islam is a religion of peace that cares for non-Muslim lives and property. The examples he gives are genuine, but he omits a crucial fact. Only Jews and Christians (and later, Zoroastrians in Iran) are entitled to protection within a Muslim state or empire. Qadri calls them “citizens”, but the truth is that only Muslims can be regarded in that light. Jews and Christians are dhimmi peoples, tolerated under certain humiliating conditions. They are somewhat favoured on account of their having been sent scriptures and prophets, but disfavoured because they have not accepted Allah, or God’s last prophet, Muhammad. Moreover, if they initially resist Muslim invaders, they must be fought through a jihad war. Once defeated, they only have the right to keep their lives, property, and places of worship on payment of a special tax known as jizya, a form of protection money. They are also forced to live under severe restrictions, penalties and mistreatment designed to humiliate them and keep them in their place as the inferiors of Muslims. By not speaking of dhimmitude, the payment of jizya, or more than one thousand years of vulnerability of Christian nations to jihad wars, Qadri again pulls the wool over unquestioning, if well-meaning, eyes of non-Muslims.

So what exactly is Qadri up to? He is concealing important information and distorting the Arabic vocabulary in order to drive home a narrative of Islam’s deep connection to peace and security. His strictures against terrorism are sincere and valuable, yet his whitewashing of historical, legal and scriptural treatment of non-Muslims and the actual practice of jihad only serves to perpetuate a myth.

Qadri and many others who adopt this position are, sadly, engaged in setting up a smokescreen. The tactic, as a comment explains, may be found online:

“To get people to believe in two contradictory beliefs, present them both as part of a larger belief system where it is more important to accept the whole system than question ‘minor’ inconsistencies within it.”

That, surely, is exactly how Qadri and so many others (even members of America’s left-leaning parties) come to function.

It is crucial to be able to see and identify this smokescreen if we do not want to throw the baby (opposition to Islamic terrorism) out with the bathwater (whitewashing the truth). Nevertheless, it is vital to expose and to challenge it if we are ever to come to terms with the true nature of Islam as an expansionist, religio-political ideology.

When Muhammad Tahir-ul-Qadri conceals important information and distorts Arabic vocabulary in order to drive home a narrative of Islam’s deep connection to peace and security, he is engaged in setting up a smokescreen. (Image source: ServingIslam/Wikimedia Commons) |

Dr. Denis MacEoin has spent a lifetime studying Islam and related matters. He has been a Distinguished Senior Fellow at the Gatestone Institute since 2014.