he EU vs. the Nation State? by George Igler

- The question remains, however, why any nation would want to throw out its sovereignty to institutions that are fundamentally unaccountable, that provide no mechanism for reversing direction, and whose only “solution” to problems involves arrogating to itself ever more authoritarian, rather than democratically legitimate, power.

-

- Previous worries over unemployment and the economy have been side-lined: the issues now vexing European voters the most, according to the EU’s own figures, are mass immigration (45%) and terrorism (32%).

- The Netherlands’ Partij Voor de Vrijheid, France’s Front National and Germany’s Alternativ für Deutschland are each pushing for a referendum on EU membership in their respective nations.

- Given that the EU’s institutions have been so instrumental as a causal factor in the mass migration and terrorism that are now dominating the minds of national electorates, some might argue that the sooner Europeans get rid of the EU, which is now doing more harm than good, the better.

Attention is beginning to focus on elections due to take place in three separate European countries in 2017. The outcomes in the Netherlands, France and Germany will determine the likely future of the European Union (EU).

In the Netherlands, on March 15, all 150 members of the country’s House of Representatives will face the ballot box. The nation is currently led by Prime Minister Mark Rutte, whose VVD party holds 40 seats in the legislative chamber, ruling in a coalition with the Dutch Labour party, which holds 35 seats.

In contrast, the Party for Freedom – Partij Voor de Vrijheid (PVV) – led by Geert Wilders, currently holds 12 seats.

According to an opinion poll, issued on December 21, Wilders’s party has leapt to 24% in the polls, while Rutte’s party has slid to 15%. Were an election to happen now, this would translate to 23 MPs for Rutte’s VVD, and 36 MPs for Wilders’s PVV.

Given the strict formula of proportional representation in the Netherlands, however, coalition governments are the norm. Should Wilders’s PVV come first in March, he will likely need to negotiate with one of his staunchest critics to form a government.

In France, two rounds of voting in the presidential elections are set to take place on April 23 and May 7 – with the two leading candidates from the first round facing each other in a runoff in the second round.

The most likely candidates to make it through to the second round, François Fillon, of the centre-right Les Républicains, and Marine Le Pen, of the populist Front National, remain tied in first-round polling.

A survey, published on December 7, gave each candidate 24%. Le Pen’s party, however, has previously fallen afoul of France’s dual-round voting system, in which voters for other parties have used the second round to swing behind the more moderate candidate.

A separate BVA poll, which solely simulated a run off between Fillon and Le Pen, showed the former the potential victor by 67%.

For all the discussion of a populist revolt in European politics, the parties agitating for change against the continent’s open borders, and its centralized, unaccountable and un-transparent law-making – originating from the institutions of the EU – continue to face an uphill climb.

In Germany, despite the calamities associated with the decision of its Chancellor, Angela Merkel, to accept 1.5 million Muslim migrants into her nation in 2015, she is seeking re-election.

On a date yet to be determined, between August 27 and October 22, German federal elections will take place to decide the members of the Bundestag, the country’s federal parliament.

Despite having been founded only in April 2013, the populist Alternative for Germany party – Alternativ für Deutschland (AfD) – has recently risen to an unprecedented 16% in the polls, in the wake of the attack on Berlin Christmas shoppers on December 19. Terrorism is proving a driver of voters’ intentions.

The increasing levels of support being enjoyed by Europe’s populist Eurosceptic parties are clearly associated with issues which are coming to dominate popular concern. Previous worries over unemployment and the economy have been side-lined: the issues now vexing European voters the most, according to the EU’s own figures (pp.4-5), are mass immigration (45%) and terrorism (32%).

Breaking these Eurobarometer numbers down further, country by country (p.7), Dutch voters picked immigration as their greatest concern by a startling 56%, with terrorism following at 33%.

French voters, despite being subjected to more recent terrorist atrocities than any other European nation, picked immigration and terrorism by a margin of 36% and 35%, respectively, according to the latest EU report. The parlous state of the French economy continues to be a major concern to French voters.

The elections scheduled next year in the Netherlands, France, and Germany, are doubly significant in that they make up three of the six original signatory nations of the founding treaty which eventually gave rise to the EU.

The Netherlands’ Partij Voor de Vrijheid, France’s Front National and Germany’s Alternativ für Deutschland are each pushing for a referendum on EU membership in their respective nations.

Signed in March 1957, by Italy, France, West Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg, the Treaty of Rome established both the European Economic Community – proposing a single market for goods, labour, services and capital within the bloc – and also, crucially, brought the European Commission into existence.

The executive body of the EU, which also has the sole remit for initiating legislation at the European level, is led by the controversial Jean-Claude Juncker, whose own grim opinion of the nation state’s role in the likely future of the European continent was made clear in a speech on December 9.

On the 25th anniversary of the drafting of the Maastricht Treaty, which paved the way for the Euro – the single currency shared by 19 countries within the 28 member EU – Mr. Juncker delivered a stark message:

Europe is the smallest continent. … We are a relevant part of the global economy: 25% of the global GPD. In 10 years from now, it will be 15%. In 20 years from now, not one single Member State of the European Union will be a member of the G7. … And from a demographic point of view, we are not really disappearing, but we are losing demographic weight.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Europeans represented 20% of the human kind. Now, at the beginning of this century: 7%. At the end of this century: 4% out of 10 billion people. So those who do think that time has come to deconstruct, to put Europe in pieces, to subdivide us in national divisions, are totally wrong. We will not exist as single nations without the European Union.

In short, according to Juncker, the European nation state simply no longer has a future. Many, including voters this year in Britain and Italy, and potential supporters of the PVV, the AfD and the Front National, would emphatically disagree.

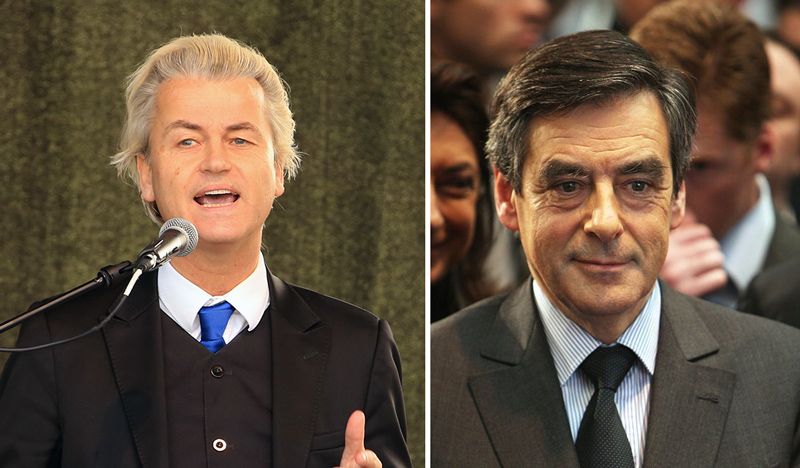

In the 2017 elections in the Netherlands and France, Geert Wilders (left) and François Fillon (right) have good chances of being elected. |

Critics of the EU, whose philosophical foundations were laid between the two World Wars, have often claimed that its purpose was to tie together the economic fortunes of each member state so that exiting the bloc would become practicably impossible.

As one of the founding fathers of the EU, the French diplomat Jean Monnet, argued in 1943:

“There will be no peace in Europe if states are reconstituted on a basis of national sovereignty … Prosperity and vital social progress will remain elusive until the nations of Europe form a federation or a ‘European entity’ which will forge them into a single economic unit.” [1]

This “fusion of (economic functions),” Monnet explained in 1952, “would compel nations to fuse their sovereignty into that of a single European State.” [2]

Despite the historic vote by the United Kingdom to exit the EU on June 23, the procedural mechanism for Britain’s departure has yet to be implemented, and has been the subject of extended legal and parliamentary debate.

Those who had hoped that Britain would have already demonstrated a clear economic future for a nation outside the EU bloc, to embolden populist parties in other European countries seeking independence, before next year’s pivotal elections, have had their wishes caught up, temporarily at least, in the cogs of procedure.

The question remains, however, why any nation would want to throw out its sovereignty to institutions that are fundamentally unaccountable, that provide no mechanism for reversing direction, and whose only “solution” to problems involves arrogating to itself ever more authoritarian, rather than democratically legitimate, power.

However, the EU claims that support for the euro within the currency bloc is at an all-time high (70%), and a majority in countries like Hungary, Romania and Croatia would, in fact, like to join the EU’s currency union.

Given that concerns about mass migration, and the increase in crime and terrorism that have accompanied it, are only likely to grow, and that cross-national security cooperation is necessarily undermined by the EU’s open internal borders – Anis Amri, the Berlin truck assassin, was shot dead in Milan – Europe’s populist parties nevertheless face a sizeable challenge.

Despite voters’ concerns about mass migration, in the absence of presenting their electorates with a compelling economic vision outside of the EU, polling numbers still favour the political mainstream.

Given that the EU’s institutions have been so instrumental as a causal factor in the mass migration and terrorism that are now dominating the minds of national electorates, some might argue that the sooner Europeans get rid of the EU, which is now doing more harm than good, the better.

George Igler, between 2010 and 2016, aided those facing death across Europe for criticizing Islam.