A Few Questions for London’s New Mayor and Other Luminaries by Robbie Travers

- London Mayor Sadiq Khan has called moderate Muslims “Uncle Toms” – not quite what one would expect to hear from a supposed advocate of equality.

-

- The irony of course is that to show you are not a racist, you are using racist terminology. Is that what an anti-racist should sound like?

- Name-calling is usually just a form political blackmail designed to close down a discussion before it has even begun. What it does not wish to take into consideration is that someone might simply have a different opinion.

- Every candidate’s record on terrorism should be questioned. It is the public’s right. Just because Khan happens to be Muslim, does that entitle him to special treatment? Why should one not be able to ask Khan the same questions one might ask any other politician?

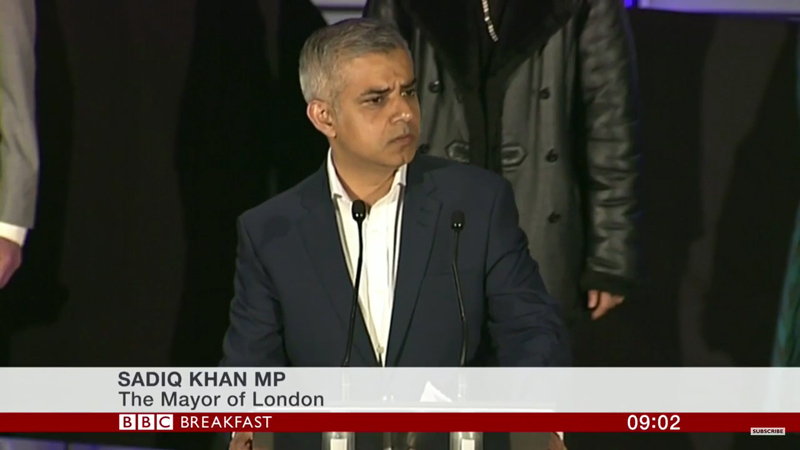

Many are hailing the election of London’s new mayor, Sadiq Khan, admirably the “son of a Pakistani bus driver,” as the sign of a new, tolerant London and that Britain’s Black and minority ethnic communities are making progress.

But there are concerns. Khan has called moderate Muslims “Uncle Toms” – not quite what one would expect to hear from a supposed advocate of equality.

The irony of course is that to show you are not a racist, you are using racist terminology. Is that what an anti-racist should sound like?

Branding someone an “Uncle Tom” also implies that the poor primate cannot think independently or formulate an opinion apart from his ethnicity. Basically, the accusation would seem an attempt to intimidate those within a community to conform to whatever the group-think is; anyone who disagrees must therefore be a traitor. But name-calling is usually just a form political blackmail designed to close down discussion before it even begins. It seemingly does not wish to take into account that someone might just have a different opinion.

It is unfortunate that the Mayor of London, a city of such diversity of both opinions and demographics, would use such terminology to suggest that Muslims who disagree with the more conservative interpretation of Islam are possibly traitors to their religion.

In fairness, Khan has stated that he “regretted” using the term. It is refreshing that a politician took the responsibility to apologize, but might there nevertheless be room for a few candid questions?

Does Khan believe, for instance, that law-abiding, moderate British Muslims are disloyal to their community for holding views that might differ from those of the majority? Also, does he think that using terminology such as “Uncle Tom” makes it more difficult for liberal or progressive Muslims to promote reform within their community? In fact, what does Khan think of the idea of reforming or reinterpreting Islam?

Earlier, in 2006, Khan defended London’s mayor at the time, Ken Livingstone, now suspended from the Labour Party “for bringing the party into disrepute” after MPs accused of him of antisemitism and making offensive comments about Hitler supporting Zionism.

Khan has since condemned Livingstone for remarks made about the Holocaust, and even added:

“I accept that the comments that Ken Livingstone has made makes it more difficult for Londoners of Jewish faith to feel that the Labour party is a place for them, and so I will carry on doing what I have always been doing, which is to speak for everyone.”

It is certainly promising that, as his first official event since attaining office, Khan attended a Holocaust memorial event, and said that Labour has not done enough to tackle antisemitism.

Well then, how, within Labour, does he plan to tackle the rising antisemitism?

Khan’s judgement about advisers, however, has also raised concerns. Khan’s former top adviser, Shueb Salar, began working for him in 2014, when Khan was Shadow Justice Secretary and Shadow Minister for London. Salar’s duties included “assisting in the drafting of speeches, reports, press releases, briefings, parliamentary questions, letters and email correspondence.”

Yet, while Labour’s own written material claimed that “Labour means fighting for “fairness, justice and for equality, Salar tweeted about a same-sex couple travelling on London’s Underground system: “Had the funniest tube journey ever, some rowdy chavs were cussing these 2 gay guys kissing LOL maybe they deserved it.”

Did he mean that assaulting same-sex couples is acceptable and to be expected? He also made other remarks that could be construed as homophobic.[1]

In the wake of polls illustrating that 52% of UK Muslims think that homosexuality should be illegal, what does Khan think of views such as this?

On another topic, a few years ago, in 2004, Khan shared a platform with five Islamic extremists at an event sponsored by Al-Aqsa, and featuring “gender segregation.” The organization has published materials by Holocaust denier Paul Eisen which challenge “the ideological, spiritual and religious meaning of the Holocaust narrative and the use to which it has been put to enforce Jewish power.” What does Khan think about the Holocaust, the views of Al-Aqsa, Eisen and gender segregation?

In 2004, when Khan was chair of the Muslim Council of Britain’s legal affairs committee, he commented on remarks by the Islamic theologian, Dr. Yusuf al-Qaradawi at the Select Committee on Home Affairs. The Muslim Council of Britain, which Khan represented at the hearing, had described Al-Qaradawi “a voice of reason and understanding. “

“Oh God,” al-Qaradawi had said, “deal with your enemies, the enemies of Islam. Oh God, deal with the usurpers and oppressors and tyrannical Jews. Oh God, deal with the plotters and rancorous crusaders.”

Khan responded:

“I cannot comment on the specific quote you have given but there is a consensus among Islamic scholars that Mr. al-Qardawi is not the extremist that he is painted as being by selective quotations from his remarks.”

Unfortunately, Qaradawi also cited a passage in the Hadith [the actions and sayings of Muhammad] — a passage, incidentally, that is also part of the Hamas Charter:

“The Hour will not come until the Muslims fight the Jews, with Muslims fighting them until the Jew hides behind rocks and trees, and the rocks and trees saying: ‘Oh Muslim, Oh servant of Allah, this Jew behind me, come kill him.'”

Al-Qaradawi has also stated that rape victims who dressed immodestly must be “punished,” but also that, “to be absolved from guilt, a raped woman must have shown good conduct.” Al-Qaradawi also defends female genital mutilation (FGM), a crime in the UK.

What, then, are Khan’s views on FGM, rape, anti-Semitism and Qaradawi? What, in fact, are his views on Islamic extremists?

Finally, in 2006 Khan signed a letter declaring that “the debacle in Iraq” had contributed towards terrorism affecting the UK. It is not clear if Khan was suggesting that British foreign policy actively creates terrorism, or if British Muslims, angered by the alleged murder of innocent Muslims in the Middle East, think that the best way to counter British foreign policy is to kill more innocents in the Middle East.

What, then, does Khan think are the main causes of terrorism? What does Khan think about Islamists and how they become radicalized?

In conclusion, why do some people suggest that asking Khan questions about Islam and Islamic extremism is somehow “Islamophobic”? Is it possible they are afraid of what the answers might be?

Shouldn’t every candidate’s record on terrorism be questioned? Is that not the public’s right? Just because Khan happens to be Muslim, should this entitle him to special treatment? Is failing to evaluate someone, using the same standards you would use to evaluate others, just because of his or her race, religion, sexual preference or gender is, not, in the broadest sense, “racist”?

Why should one not be able to ask Khan the same questions one might ask Jeremy Corbyn, David Cameron or any other politician?

Do “inconvenient” questions come about because people are racist, or because they might just be horrified by events such as the murder in Glasgow of a shopkeeper, Assad Shah, killed by another Muslim for wishing his friends a “Happy Easter” on Facebook?

Most of all, why are questions considered so dangerous that they must not even be asked?

Robbie Travers, a political commentator and consultant, is Executive Director of Agora, former media manager at the Human Security Centre, and a law student at the University of Edinburgh.