When you hear the quite horrific stories of censorship and dangerous restrictions on expression at universities in the US, the UK and Europe, your first reaction might be to laugh at how infantile the nature of political discourse in the student world has become.

Cardiff Metropolitan University banned the use of the word “man” and related phrases, to encourage the adoption of “gender neutral” language. It is the equivalent of the “newspeak” about which Orwell warned: “Ambiguous euphemistic language used chiefly in political propaganda”.

Currently, longstanding expressions carrying no prejudice are now used as the trappings of often fictitious “oppressions.”

City University in London, renowned for its journalism school, is apparently banning newspapers that do not conform to the current student body’s various political biases. If the Sun, Daily Mail and Express are such bad publications, why not allow students to read them and make up their own minds? Perhaps students do not trust their peers to make up their own minds? What if they make up their minds the “wrong” way? To suggest that the brightest and best at our universities cannot contend with a dissenting argument should probably be at least slightly concerning.

There seems to be a growing consensus among student populations that certain views should not be challenged, heard or — if one does not hear them — even known.

A culture has also emerged at universities of promoting “safe spaces”. These ostensibly aim to be free of prejudices such as racism, anti-Semitism, misogyny and other bile. But all too often, we have seen them filled with exactly these prejudices – anti-whiteness, anti-maleness and of course anti-Semitism, as even some of Britain’s leading universities are “becoming no-go zones for Jews“.

We have seen the staff of the satirical French magazine Charlie Hebdo slaughtered by ISIS terrorists for mocking Mohammad, and banned from Bristol and Manchester University, apparently because some students might find it offensive. What about the delicate sensibilities of those of us who find censorship offensive? Especially of a publication that has stood up to religious fanaticism and paid the ultimate price? Where are the “safe spaces” for those who would ban banning?

At the University of Edinburgh, a student official was silenced for raising her hand — as if a raised hand were a “thought crime” tantamount to physical violence. Yet, as Sigmund Freud said, “The first human being who hurled an insult instead of a stone was the founder of civilisation.”

Does mean, then, that many campuses are going back to pre-civilisation? Last year, the magazine Spiked found that 90% of British universities hold policies that support censorship and chill free speech. In February, riots to disrupt a speech at University of California, Berkeley caused $100,000 worth of damage — but only one person was arrested.

Do the advocates of suppressing speech not see — or care — where silencing free speech leads? You set a precedent that allows further silencing, which, in turn, creates ever-expanding censorships. One imagines that especially universities should be the institutions that protect the exchange of ideas.

Historically, contrarian views — such as those of Giordano Bruno, Galileo, Darwin, Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi, Servetus, Oldenburg, Domagk and Freud — have been essential to shaping our culture. They have reversed accepted practices and opened minds. Where would our culture be without the freedom to question, be creative or even at times offend?

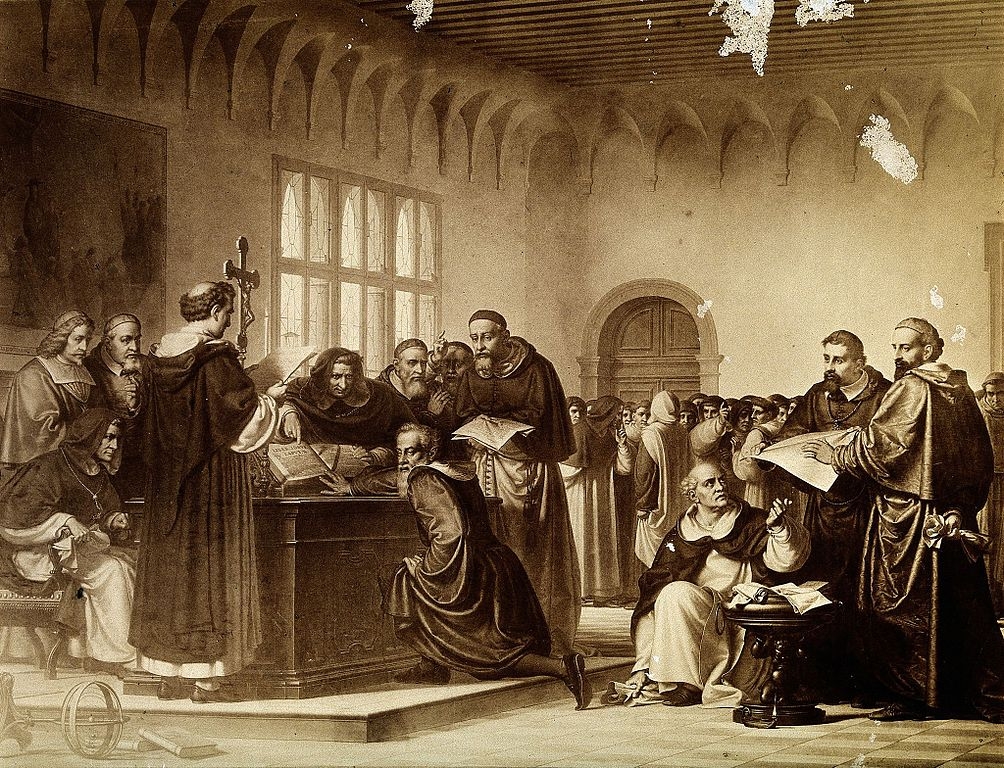

Where would our culture be without the freedom to question, be creative or even at times offend? Pictured: Galileo Galilei at his trial by the Inquisition in Rome in 1633. (Image source: Wellcome Trust/Wikimedia Commons) Where would our culture be without the freedom to question, be creative or even at times offend? Pictured: Galileo Galilei at his trial by the Inquisition in Rome in 1633. (Image source: Wellcome Trust/Wikimedia Commons) |

To begin with, just about any idea can be found “offensive” by someone. To devout conservative Muslims and Christians, homosexuality may be offensive; to anti-Semites, Jews; to white racists, blacks; to black racists, whites, and so on. When we legitimise anyone’s right to be free of exposure to “offensive” ideas, we empower only authoritarians, who historically seem all too happy silence anyone over anything.

In addition, sometimes causing offence is unavoidable — or we would all still be mired in the Inquisition or, as still takes place, murdering people for sorcery.

Discussion is still probably the most constructive way to decide which ideas are worth being celebrated and which are worth rejecting.

Last week, I found myself under investigation — without evidence — for some of my political views, posted on my Facebook wall:

“Excellent news that the US administration and Trump ordered an accurate strike on an Isis network of tunnels in Afghanistan. I’m glad we could bring these barbarians a step closer to collecting their 72 virgins”.

This note was then alleged to be “blatant Islamophobia” and consequently a “hate crime.” Under UK law, that would make being a member of ISIS a protected characteristic — presently, however, it is not.

There are also claims that “ISIS has nothing to do with Islam”, yet, according to the woman who complained about my post, Esme Allman, mocking ISIS apparently makes one guilty of having “incited hatred against religious groups and protected characteristics.”

Allman also alleged that I had, “without her consent,” published “a decontextualized quote” by her, in which she had referred to “black men” as “trash.”

In the UK, however, quoting someone for criticism of their work or speech, regardless of whether their work is copyrighted, is completely legal, especially if it is intended to facilitate the “reporting of current events.” As the quote of Allman’s remark was intended to question her behaviour in a public position, the law would presumably protect it.

Moreover, her complaint alleges that my remarks regarding Trump’s strike on ISIS, noted above, induced a “state of fear and panic.” At a Western university, why would mocking a terrorist organisation that has slit throats, burned people alive, drowned people (some in boiling tar), be seen as inducing “fear and panic”? The people who commit these atrocities should be causing the fear and panic. It is our job in the West to point out what they do so that eventually they do not do it here, too.

What also should cause “fear and alarm” is that individuals are now taking it upon themselves to defend such terrorists against criticism. Members of ISIS openly despise Jews, the LGBT, women and free thinkers. Why would any individual who is supposedly championing human rights for minorities support such a death cult?

It is hoped that students, especially at a leading university, would be intellectually curious enough to withstand being alerted to what ISIS is up to. If fellow students disagree, they should be able to challenge one’s allegations through a reasoned analysis of the argument. They did not.

Another screenshot that served as the only evidence was a Facebook post in which I noted that:

“I won’t give elements of Islam or Muslims who hold regressive beliefs a free pass for their assorted poisonous bigotries and regressive values because they face bigotry. If you have terrible, oppressive views that seek to attack the rights of others, expect to be called out for those views, regardless of being oppressed yourself…”

It is essential that the culture of victimhood, in which people think they can silence others on the grounds of “identity,” is dismantled. Anyone should be able to question or criticise just about anyone, within the limits of Brandenburg v. Ohio. Free speech, according to this 1969 U.S. Supreme Court decision, is limited only if it encourages immediate and credible danger or other unlawful action. We should not care — or even know — what minority group, if any, someone belongs to. That would be racist.

Robbie Travers, a political commentator and consultant, is Executive Director of Agora, former media manager at the Human Security Centre, and a law student at the University of Edinburgh.