Does the Anti-Nepotism Statute Preclude Trump from Appointing Kushner? by Alan M. Dershowitz

The controversy over President-elect Trump’s expected appointment of his son-in-law, Jared Kushner, raises serious constitutional issues regarding the separation of powers. Congress, which holds the purse strings, may have the power to withhold the salary of a relative who the president wants as an advisor. But it is doubtful whether Congress has the constitutional power to preclude the president — who heads the executive branch — from appointing whomever he chooses as a White House advisor.

This is because the separation of powers limits the authority of any one branch to dictate to another branch how it shall conduct its government business. Accordingly, the Supreme Court of the United States does not feel bound by Congressional enactments regarding the recusal of judges for conflict of interest, or other rules of ethics enacted by Congress to constrain its judicial activities. The question of when one branch intrudes on another is often a matter of degree, but each branch guards its independence jealously.

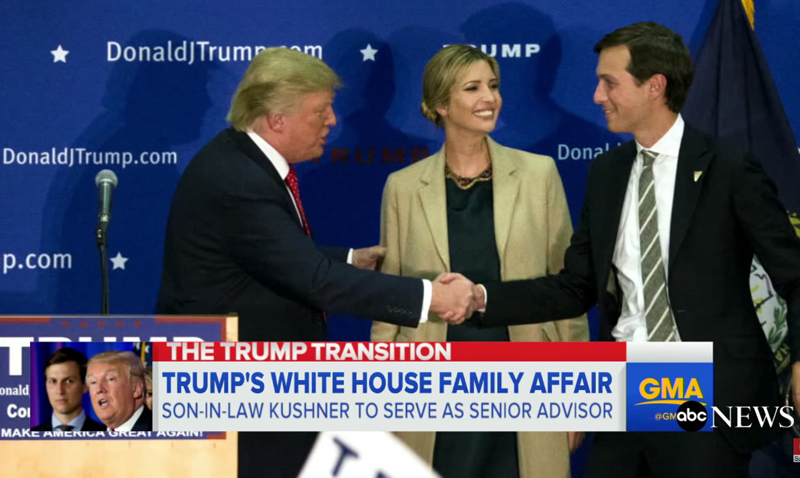

Donald Trump (left), his daughter Ivanka (center), and his son-in-law Jared Kushner (right). (Image source: ABC video screenshot) |

This constitutional issue may never reach the courts for three reasons. First, no one may have standing to challenge such a presidential appointment, especially if taxpayer money is not being spent on his salary. Second, the anti-nepotism statute can reasonably be interpreted to preclude only the payment to relatives and not any pro bono service they may render. Third, the statute can be, and has been, interpreted as not applying to White House staff.

There are two relevant provisions of the anti-nepotism statute that was enacted following President John Kennedy’s appointment of his brother Robert to be Attorney General. The first prevents “public officials” from promoting a “relative” “to a civilian position in the agency in which he is serving or over which he exercises jurisdiction or control.” [1] The second provides that “[a]n individual appointed… in violation of this section is not entitled to pay.”[2] There is an apparent conflict between these two provisions since the first appears to provide for an absolute prohibition against the appointment of relatives, whereas the second provides that if the relative is appointed he cannot be paid.

In interpreting this poorly drafted statute, a court would have to decide whether Congress intended to prevent the only evil of relatives being paid for jobs for which they have been appointed by their kin, or whether Congress was actually trying to prevent presidents from seeking the advice and council of relatives. A court considering this statute, in the context of a constitutional argument based on separation of powers, might well interpret it narrowly to preclude only the payment of salaries. It might also find it inapplicable to White House staff members, who are not part of any “agency.” Indeed, one court, in considering Hillary Clinton’s appointment by her husband to direct the White House campaign for health care, suggested that the statute did not apply to White House advisors.[3]

Courts generally interpret statutes, particularly those that are as unclear as this one, in a manner that avoids difficult constitutional questions. So I am relatively confident that President-elect Trump’s appointment of his son-in-law Jared Kushner to be a senior adviser in the white house will not be successfully challenged.

Nor should it be, as a matter of sound policy. Surely our chief executive should have the power to surround himself with anyone he believes, rightly or wrongly, can render sound advice. There are, of course, risks in the appointment of relatives. It would be more difficult for the president to fire his son-in-law — the husband of his daughter and father of his grandchildren — than it would be to fire a non-relative. But that is a factor any president should take into account in hiring a relative. I see no great institutional dangers in allowing such appointments and I do see institutional dangers in prohibiting them.

No statute could, of course, preclude a president from seeking and relying on the advice of relatives. The only question is whether the relative can receive a formal — and in this case non-paying — appointment. There are advantages to a formal appointment: it requires the appointee to avoid conflicts of interest; and it promoted visibility and accountability.

So let the president appoint his son-in-law to this important position as senior advisor and let’s all hope, for the benefit of the country, that it is wise decision. History has certainly judged President Kennedy positively for appointing his brother as Attorney General. The two of them worked closely together to end the Cuban missile crisis, to promote civil rights, and to carry out other policies that benefitted the entire nation. The statute should be amended to permit the appointment of relatives, while maintaining the prohibition on the government paying them. That would avoid the evil of financially motivated nepotistic appointments, while preserving the benefits of allowing presidents to choose advisors who they believe will be loyal and beneficial in serving the country.

Alan M. Dershowitz, Felix Frankfurter Professor of Law, Emeritus and author of “Taking the Stand: My Life in the Law and Electile Dysfunction.”